Globally, 50 million children and young people have been uprooted as a result of displacement or migration. Millions more are severely affected by the consequences of these migration movements. But where do most of these displaced people go?

There have never been as many child refugees as there are today. The rise in conflicts, the strengthening of extremist groups and authoritarian regimes, increased poverty and the growing number and severity of natural catastrophes triggered by climate change are forcing ever more people to leave their home countries. According to the most recent estimates, the number of displaced children worldwide has risen to 50 million.

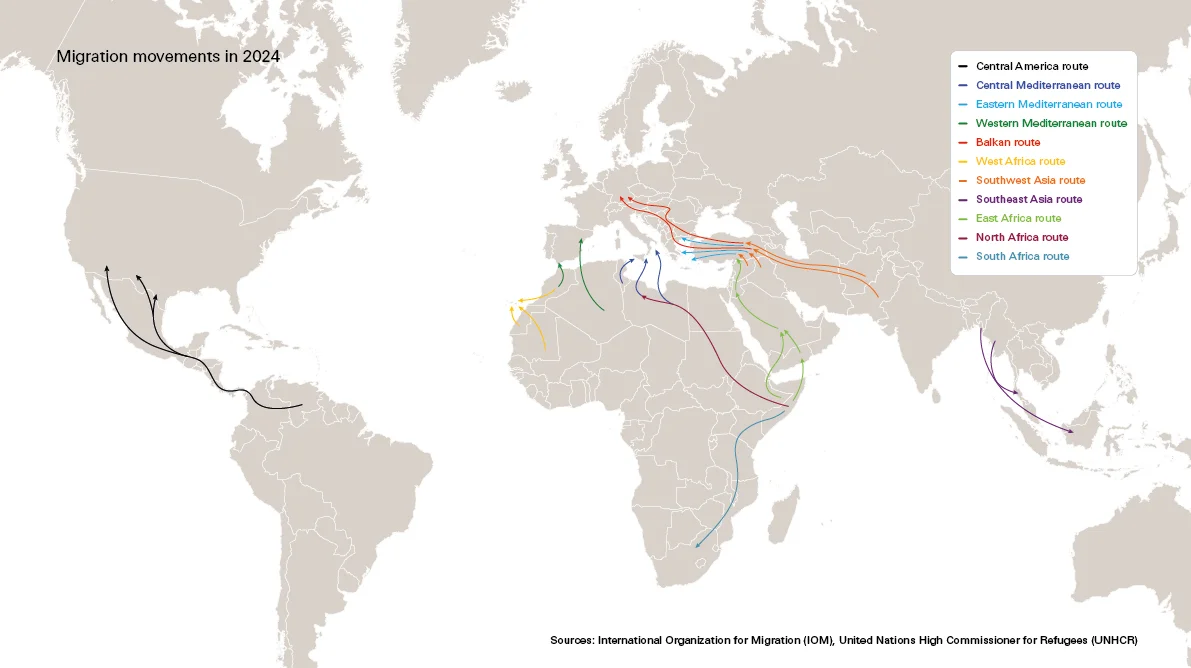

Over many years, ongoing displacement from crisis and war regions has led to the development of irregular migration routes, so-called main migration routes that are used by unusually large numbers of displaced persons. These mass migration routes give birth to complex population movements. While asylum seekers, refugees, smuggled migrants and human trafficking victims all use the same routes and modes of transport, their reasons for leaving their homes differ (“mixed migration”).

All of them have left their homelands to seek refuge somewhere else.

Migrants are people who move or have moved away from their usual place of residence, either within a country or across an international border – regardless of their legal status, their reason for moving, the duration of resettlement and whether they relocate voluntarily or involuntarily. This category also includes refugees and asylum seekers.

Refugees are persons who are granted asylum in another country because they can prove that they are being persecuted in their country on the basis of their race, religion, nationality, affiliation with a specific social group or political beliefs.

Asylum seekers are all persons seeking international protection. This definition is often also used as a legal term for someone who has applied for refugee status or another form of international protection, but is still waiting for a final decision on their status. Someone who intends to ask for asylum but has not yet submitted a formal application can also be an asylum seeker.

Terms such as “people seeking protection” or “displaced persons” are umbrella terms that include all of these people.

Mass migration routes are wrongly interpreted to be one-way streets leading from A to B. This interpretation does not, however, do justice to the complexity of migration routes. The strict policing of many main migration routes in particular often compels people seeking protection to try and reach their countries of destination via long detours. In addition, displaced persons usually use not only one, but several migration routes. Most irregular migration routes are convoluted and multi-directional, and often also very perilous.

The biggest migration routes in the world include the Central Mediterranean route, the Southwest Asia route, the East Africa route and the Central America route. Migrants following these main migration routes have to travel overland as well as by sea, and often have to traverse several countries.

Migration routes leading to the European Union (EU)

Even though the EU countries with their political and economic stability are a popular destination for people seeking protection from across the globe, refugee numbers are still low compared to the Global South. One reason for this is that fleeing people usually try to find safety in countries close to their home regions, which are mainly located in the Global South, and would also prefer to return to their homes quite soon. Also, many of them do not have the funds they would need to flee over a greater distance. And more often than not, entry restrictions applied by many transit or destination countries prevent migration to Europe.

Contrary to the widely held perception in Europe, countries of the Global South play host to almost half of all migrants and more than 75 percent of all registered refugees and internally displaced persons globally. The lion's share of global displacement movements is therefore intraregional in nature.

The Central Mediterranean route runs from various North African countries bordering on the Mediterranean, e.g., Tunisia and Libya, across the Mediterranean towards the Italian coast and beyond. This is where the migration pathways from Western, Central and Eastern Africa converge. For most displaced persons, the crossing to Italy is often just the last stage of a very long journey spanning months, and sometimes even years.

The Central Mediterranean route is one of the biggest migration routes in the world. It is also one of the deadliest: in 2023, almost 160,000 people reached Europe via this route, but UNHCR registered more than 2,000 deaths and disappearances in the central Mediterranean for the same period. The number of unreported fatalities is probably much higher, as many shipwrecks have no survivors or are not registered.

Many children also come to the European Union via the Central Mediterranean route. Looking for peace, safety and better educational and future prospects, they are exposed to great danger during every stage of their journey – mental and physical violence, exploitation, malnutrition and inadequate healthcare, separation from their parents and family members, no access to health services and forced marriage. Particularly at risk are children who travel without a responsible adult looking after them, either because they fled on their own or were separated from their caretakers during their escape. About 70 percent of children traveling to Europe via the Central Mediterranean route cross national borders on their own.

Those who survive the crossing are first taken to hot spot centers before being moved to reception centers. These hot spot centers are often fenced in and severely curtail the freedom of movement of the people living there. Ideally, asylum seekers should be moved to reception centers within 72 hours, but the system is very overwhelmed and they often have to stay in these hot spot centers for one to two months. It is particularly difficult for children who suffered abuse and violence during their flight to find suitable facilities as they often suffer from psychosocial disorders such as post-traumatic stress disorder and need special support.

There are other big migration routes crossing the ocean to the EU in addition to the Central Mediterranean route: the Western and Eastern Mediterranean routes and the West Africa route. The Western Mediterranean route runs from Morocco and Algeria to mainland Spain across the Strait of Gibraltar. The Eastern Mediterranean route runs by sea from Turkey to the Greek Aegean islands (Lesbos, Kos, etc.), and to a lesser extent also overland toward Northern Greece and Bulgaria. Migrants taking the West Africa route mainly travel to the Canary Islands from Western Sahara, Morocco and Mauritania. In 2020, around two million West Africans lived in the EU, around 40 percent of them women, which gives the lie to the popular belief that mostly men from West Africa migrate to the EU. However, women come to the EU more often under family reunion programs than via irregular migration routes such as the Mediterranean.

Some persons seeking protection come overland to the EU via the Balkan route, which consists of two sub-routes: the Western Balkan route running from Greece to North Macedonia and Serbia, and the Eastern Balkan route running from the Bosporus river in Turkey via Bulgaria and Romania along the Danube towards Serbia.

Migration routes through Asia and the Middle East

The migration movements in the Middle East are complex and highly unstable. Protracted conflicts in the past two decades, in particular in Syria, Iraq and Yemen, have triggered wide-ranging migration and displacement movements. At present, the Southwest Asia route is one of the most used migration routes in the region as well as the world. Economic and political factors in particular have led to irregular and mixed migration streams within the region, towards the region and from the region, among others from Syria, Iraq, Iran, Afghanistan and Pakistan to Turkey, and often further to the European Union.

In order to cross the borders on this route without being detected, many of those seeking protection have to rely on smugglers, who are often unscrupulous. The risk of becoming victims of exploitation and physical and mental violence is particularly great. According to studies by UNODC, a substantial percentage of child trafficking takes place in the migration context: smugglers and human traffickers exploit the vulnerability of the children to their own advantage and compel them into forced labor and prostitution.

In addition to the Southwest Asia route, there is another mass migration route through Asia – the Southeast Asia route. Here, people seeking protection, from countries including Myanmar and Bangladesh, try to cross the Andaman Sea and the Strait of Malacca to the coastal regions of Indonesia, Thailand and Malaysia.

Migration routes through Africa and the Middle East

Contrary to the widely held perception, the lion’s share of African migration takes place within the continent. Migrants mainly leave their homes to look for work in their neighboring countries.

As mentioned above, the biggest mass migration routes in West and North Africa are the North Africa route and the Central Mediterranean route leading to Europe. However, East Africa and the Horn of Africa also experience high migration mobility. A combination of sustained and recurring conflicts, persecution, widespread regional poverty, environmental factors such as long periods of drought and a desire for a better future contribute to complex population movements. Migration from this region follows three main migration routes: the eastern route towards Yemen and the Gulf states, the southern route towards South Africa, and the northern route towards North Africa.

The East Africa route is one of the world’s most used and deadliest migration routes. This is the route by land and sea from the Horn of Africa going towards Yemen, the Middle East and beyond. Starting in the Horn of Africa, many migrants depart from the coast of Djibouti and Somalia and cross the Gulf of Aden towards Yemen. A small number remain in Yemen, where they either apply for asylum or look for work. The majority, however, wish to cross the country to get to the neighboring Gulf states, in particular Saudi Arabia. In spite of the dangers of crossing the Gulf of Aden in unseaworthy ships, the threat posed by the conflict in Yemen and the strict controls at the Saudi Arabian border, Yemen registered more than 92,000 arrivals in 2023. The actual number of people moving along this route is probably much higher. The prolonged conflict in Yemen, which restricts access to the coast, makes it quite difficult to record the exact numbers of arrivals.

But not everybody leaves the mainland in Djibouti and Somali, like this six-year-old Ethiopian girl:

The predominantly overland southern route runs from the Horn of Africa through Kenya, Tanzania, Malawi, Zambia and Zimbabwe towards South Africa.

The northern route is the overland route running from the Horn of Africa through Sudan, Egypt and Libya. This movement converges in North Africa with streams of refugees and migrants from West Africa moving along the Central Mediterranean route. As a result of the conflict in Sudan in particular, which erupted in April one year ago, the number of people using this route is increasing again.

Migration routes through the Americas

The migration streams through Mexico and Central America are diverse and closely interlinked. Many countries simultaneously serve as countries of origin, transit and destination. Every day children and families leave their homes in South and Central America to brave the dangerous journey to the north. The reasons for this migration movement are manifold: apart from extreme poverty, ever-present violence and a lack of education opportunities, the desire for reunion with family members who previously emigrated motivates many people to embark on this long voyage.

Many of the poorest and most disadvantaged families in the region cannot use the safe and regular migration pathways and therefore choose the dangerous irregular migration routes. The biggest in this region is the Central America route running from countries in South America through Central American countries such as Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador towards Mexico and the United States. While traveling, children and families are constantly exposed to the threat of exploitation and imprisonment – a threat that also does not end after they have crossed the border. Unaccompanied children and women are most at risk of becoming victims of human traffickers, criminal gangs or brutal security forces.

During the voyage, many families and children are imprisoned or deported to their countries of origin. Back in their homeland, their living conditions are often worse than before they left: Many have taken on heavy debts to finance their trip, and children often suffer from the consequences of imprisonment or deportation. They are frequently stigmatized by their communities and are seen as losers. The threat of violence also remains. Unaccompanied minors are particularly at risk. In many instances they do not have a home to return to, and become the targets of criminal gangs. In such a hopeless situation it is very likely that they will try again to go north.

It is estimated that more than 105,000 children passed through Guatemala from January to September 2023 – this corresponds to around 400 children per day. The people mostly come from Venezuela, Cuba, Ecuador, Haiti and Colombia.

Children on the move: How UNICEF helps

Migration and displacement significantly shape the reality of life for millions of children around the world. On their frequently dangerous journeys they cross borders, continents and oceans, and often suffer grave violations of their rights. The suffering and exclusion of migrant and displaced children is not only unacceptable; it is also avoidable. A child is a child, regardless of their origin and migration status. All children have the same universal rights to protection and care. That is why UNICEF applies a holistic approach: in addition to combating the causes of migration movements, we champion the protection of children along their migration routes as well as in their countries of origin and destination.

“Migrant rights are human rights. They must be respected without discrimination – and irrespective of whether their movement is forced, voluntary or formally authorized. We must do everything possible to prevent the loss of life – as a humanitarian imperative and a moral and legal obligation.”

To sustainably combat the causes of child migration, UNICEF works closely with the countries of origin. UNICEF applies a wide range of measures such as educational programs, water, sanitation and hygiene services (WASH) and child protection systems to improve the situation of children in their countries of origin and thus ensure that they do not need to leave their homes.

Along the migration routes and in particular in the refugee camps, UNICEF provides the children with lifesaving emergency supplies such as water, food and clothing, and gives them access to services such as psychosocial support, child protection and educational programs – regardless of their legal status or the status of their parents. UNICEF also provides “Child Friendly Spaces” – safe areas where children can play, and mothers can relax and feed their babies in peace. UNICEF also helps to improve the care provided to unaccompanied children and young people who have been separated from their parents, and informs them about the services that are available. In addition, UNICEF appeals to governments to find long-term solutions that respect children’s rights, establish safe and legal migration routes for children, and avoid separating children from their parents whenever possible.

Upon arrival in their country of destination, many children face a wide array of new challenges, such as having to adapt to a new culture, learn a new language, and cope with the experiences undergone while fleeing. UNICEF therefore campaigns for the long-term integration of refugee and migrant children in the host countries and helps to strengthen national child protection systems. UNICEF also supports the return of children under family reunification programs and their reintegration in their countries of origin.